חשיפה: עידו נאור, המומחה הישראלי לאבטחת סייבר, התבקש על ידי המוסד לחדור לקספרסקי ולבצע פעולות ריגול, ככל הנראה כנגד אחד הלקוחות הגדולים שלה, איראן. הוא סירב.

Israeli cyber-security researcher, Ido Naor, runs his own company, Security Joes, helping businesses protect their cyber-infrastructure from attack. He also lectures at Bar Ilan University. Between 2015-2019, he was Kaspersky Labs’ Israel representative. He’s written an e-book about his experience, called An Ordinary Hacker. It relates an attempt to recruit him by Mossad agents to work on Israel’s behalf within the company. This is the first media account of its kind describing Mossad recruitment of Israelis to infiltrate a foreign cyber-security company. Though I’m certain meetings and efforts like this one have happened hundreds, if not thousands of times as Israel seeks to penetrate the Iranian cyber-realm.

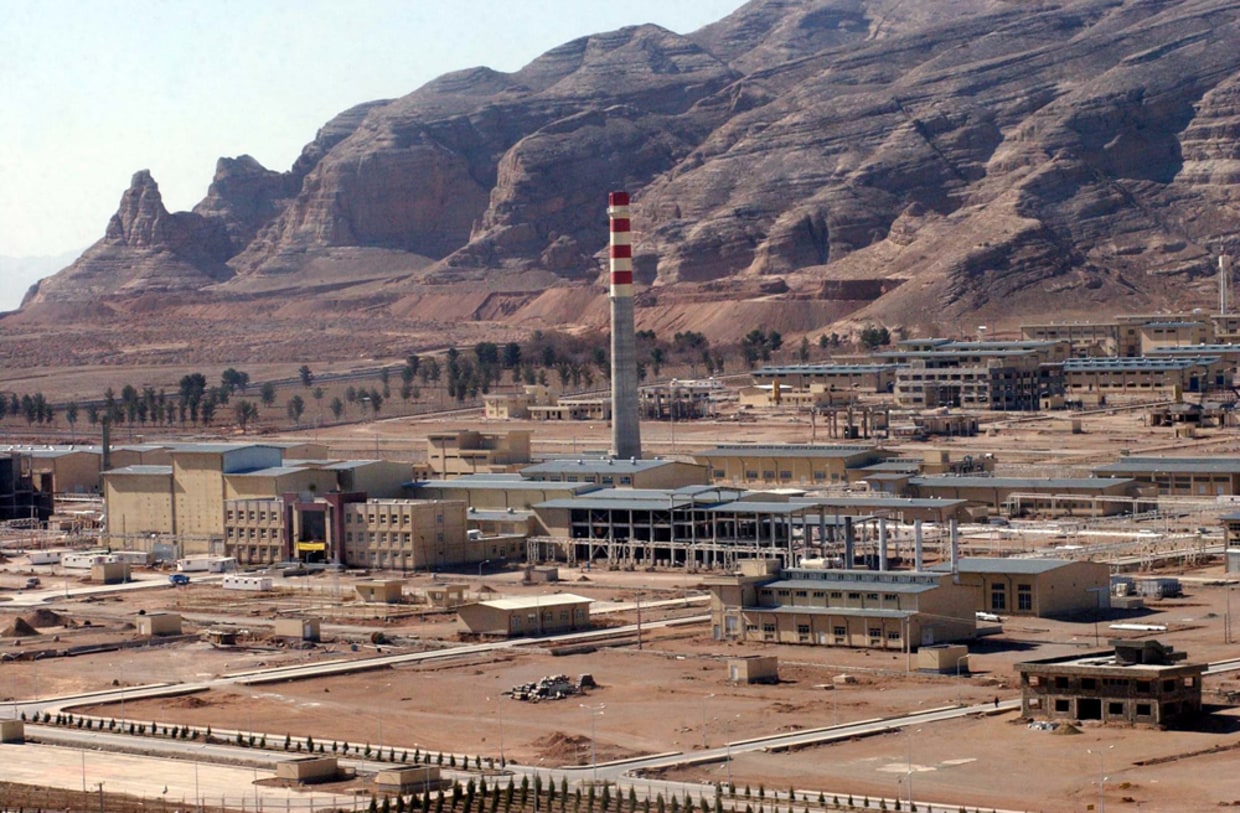

Naor doesn’t say what they expected of him. It’s possible that they elabortaed on this, but he decided not to reveal this part of the conversation. But we can guess why Naor would prove valuable inside the company. Israel has hacked Kaspersky over the past decade, because its anti-virus software is a gold-mine for Black Hats seeking access to computer systems. Compromising the software permits an intruder to gain complete control over a PC. Further, though Kaspersky’s products are used by customers around the world, it has worked closely with countries Israel considers its enemy: notably Iran. In fact, it was Kaspersky which helped Iran determine that a Russian contractor had introduced the flash drive to the Natanz nuclear facility which permitted the US and Israel to infect the software which controlled its nuclear centrifuges. The malware, Stuxnet, destroyed a large portion of the vessels and caused a significant delay in Iran’s nuclear program. Kaspersky also analyzed Israeli malware infecting Iran’s nuclear infrastructure and publicized the danger it posed, calling it the equivalent of a “biological weapon.” This did not endear the company to Israeli cyber-intelligence officials. So Kaspersky’s Iran connection alone would an employee like Naor extremely valuable to Israeli intelligence.

In his book, Naor describes the Mossad approach and subsequent meeting:

During a routine trip in Tel Aviv with Ortal [his spouse] and the girls, while driving, an unknown number flashed on my cell phone screen. I decided to answer it. On the line was a Mossad agent named G. who told me that my name had come up on some list and he was interested to talk with me. He instructed me to meet him at a well-known office building in the center of Tel Aviv.

As a former intelligence officer, former defense ministry employee and cyber expert who worked closely with the cyber and special units of the police, I wasn’t intimidated by the authoritativeness of the mystery voice. I responded to his request despite quite a few question marks which came to mind.

I made my way to the office a few days later. In the elevator that took me to the highest floor of the office building, I began to imagine the small rooms into which I would soon enter. The same sorts of rooms we used in the army in order to interview [intelligence] assets. Suddenly, I got it. I intended shortly to fly to Moscow. They surely wanted to understand why.

I entered the little room. G. and another guy awaited me there. They began to interrogate me about my background in computers and my decision to work for a Russian company [he doesn’t identify the company, but I have confirmed that it is Kaspersky]. I felt that they were a bit rude. Their penetration of my private life didn’t sit well with me. On the other hand, I wanted to draw them out in conversation in order to understand why they knew about me. Were they verifying information or did they not have a clue about me, so I would have to spoon-feed them?

After 30 minutes of conversation, I could confirm that they knew plenty about me. They confirmed with me what they already knew and where I cut corners, they corrected me with a penetrating question. It was a battle of minds. The three of us knew that this interrogation wasn’t like the ones they were used to. Despite that, they worked it in an impressive manner. Finally came the punch line:

“We want you to work with us to serve your country.”

“My friend, I’ve already given it six years of my life,” I responded with some chutzpah.

He remained calm and asked if I wouldn’t want to continue being on the nation’s side. I answered that I always would do so. But now I wore a different hat: I use my skills in the cyber-world in order to contribute to the State of Israel.

“We want you to fly to your Russian company [in Moscow] and ask a few questions for us.” They weren’t letting up. “We thought that you might also perform a few other jobs for us, if you’re interested.”

I turned to G. again dismissively, but he remained unmoved. We both knew this was a performance.

“Right now, the company which you’re talking about is the source of my income and what pays for my childrens’ schooling. What you’re telling me is that in order to be a patriot, I would have to endanger my livelihood?” I couldn’t be more blunt. A typical Israeli.

“I can’t tell you what to do. These are your own considerations,” G. answered.

That’s where he lost me. His shoot-from-the-hip response ended the discussion. Had he considered taking a different approach and tried to massage my ego, perhaps we could have come to some understanding, in which I might find myself participating in some secret operation for the Mossad amid the snowy plains of Russia.

Everything I said was recorded in a folder, including my declaration that I was not interested in being a foreign agent for Mossad. I left the makeshift office and I returned to my normal life.

This meeting was my second with the Mossad. The first had been during my army service, when we joined in an operation of a special forces unit of the Mossad. Details of the operation are secret.

U.S. intel officials slam Kaspersky while CEO calls fears of Russian influence ‘unfounded conspiracy theories’ | Cyber Scoop – May 2017 |

Kaspersky Lab has publicly reported on alleged Russian cyber espionage campaigns including Red October, a 2013 campaign spying on diplomats in Eastern Europe. The company also has reported on U.S. cyber-espionage including Stuxnet, the NSA’s 2009 hacking campaign against Iranian nuclear facility. [Joint effort Israel and role Germany’s Siemens]

Multiple American media outlets have reported that Kaspersky has also turned down American intelligence attempts to turn him into an asset for the U.S., another move that stoked annoyance from Washington.

US/NATO changed policy to reset Cold War propaganda and deem Russia as an existential threat to the West. “Making Russia a pariah state.”

“Multiple American media outlets have reported that Kaspersky has also turned down American intelligence attempts to turn him into an asset for the U.S”

So the intelligence agencies of both Israel and the United States have tried to recruit assets from within Kaspersky.

Shocking.

@ Boss: Your point being?

You quite conveniently elided the criticial last phrase in the quotation (and didn’t even offer a source for it). In full it reads:

In other words, a significant part of the hostility of both the US and Israel toward Kaspersky is that it exposes and frustrates their spying efforts.

The difference between Naor and Kaspersky is that the CIA attempted to recruit a Russian citizen to betray his country; while the Mossad recruited Naor on behalf of his country.

Now I wonder whether the bad news about Kaspersky’s anti-virus software a few years ago was no more than a US or Israeli propaganda campaign.