Today is Yom Kippur, a day of contemplation and personal accounting. A sacred day on the Jewish calendar. Today is the day you consider what you’ve done as a person and what Jews have done as a people during the past year. And you resolve to do better.

I, like all of us, have things both of which I am proud and things I regret. As Jews, we also have done things of which we should be proud and of which we should not. As a Jew, I cannot be proud of an Israel that occupies another people and disenfranchises 20% of its own Israeli-Palestinian citizens.

These are the Days of Awe. The days of teshuvah (“returning” or “repentance”). Our tradition says if we repent sincerely for our sins we may be forgiven. But to repent we must understand what we have done. Most Jews do not. Or if they understand, they understand to a degree, but not fully. That is one of the goals of this blog. To lay the predicament out for as many of my fellow Jews as I can.

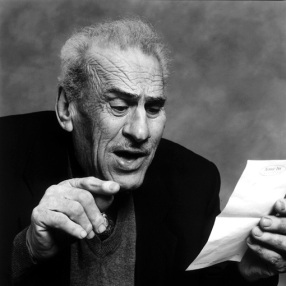

Tonight, partly in a spirit of teshuvah, partly in a spirit of tribute to a great Israeli poet who is gone, I offer this tribute to Taha Muhammad Ali.

In a similar spirit, I offer this poem from the collection, Jerusalem 1967, by the great Israeli poet, Yehuda Amichai. It is a poem that is wise about Jewish history and wise about Israel’s relation to the Diaspora. A poem written just after the 1967 War that begins to grapple with what the Palestinian means to Israel. But an imperfect poem, because most Israelis at that time did not understand what Occupation would mean. But it is still a poem that is struggling with the issue, and for that reason it is worthy of consideration on this Yom Kippur.

For many years, I was a graduate student in Hebrew literature and studied at several of this country’s best programs as well as the Hebrew University. But I never came face to face with Palestinian literature. And some of Israel’s finest writers are Palestinians writing in both Arabic and Hebrew.

Israel, of course does not generally honor its Palestinian writers with the high accolades it offers its Jewish ones. By my rough count, there have been three Israel Prizes for such figures in the sixty plus years of the state and only one for a writer. And none for Mahmoud Darwish or even a contemporary writer in Hebrew like Sayed Kashua (at least not yet). Israelis seem allergic to the idea that a great national poet might write in another language than Hebrew. The very notion offends the classical Zionist upbringing of most Israelis.

That’s why I’m especially grateful that when Ori Nir sent me notice a few days ago of Ali’s death he didn’t write, as many Israelis would, “one of Israel’s greatest Arab poets.” He wrote “one of Israel’s greatest poets.” It’s terribly important not to make such distinctions.

Watch the full episode. See more PBS NewsHour.

So I’d like to rectify the inadequacy of my earlier education by memorializing one of Israel’s greatest poets, Taha Muhammad Ali, who passed away this week at the age of 80. Since many of my readers, especially those who are not Arabic-fluent, may not be familiar with Ali, I quote this short biographical passage.

Taha Muhammad Ali was born in 1931 in a village in Galilee, Saffuriya, in Mandatory Palestine. At seventeen, he fled to Lebanon with his family after the village came under heavy bombardment during the Arab-Israeli war of 1948. A year later he slipped back across the border with his family and settled in Nazareth, where he has lived ever since.

In the fifties and sixties, he sold souvenirs during the day and studied poetry (everything from classical Arabic to contemporary American free-verse) at night. Still owner of a small souvenir/antiques shop he operates with his sons, he writes vividly of his childhood in Saffuriya and of the political upheavals he has survived.

The Saffuriya of his youth has served as the nexus of his poetry and fiction, which are grounded in everyday experience and driven by a storyteller’s vivid imagination. He is self-taught and began his poetry career late.

Taha Muhammad Ali writes in a forceful and direct style, with disarming humor and an unflinching, at times painfully honest approach; his poetry’s apparent simplicity and homespun truths conceal the subtle grafting of classical Arabic onto colloquial forms of expression. In Israel, in the West Bank and Gaza, and in Europe and in America, audiences have been powerfully moved his poems of political complexity and humanity. He has published several collections of poetry and is also a short story writer.

Ali’s Israeli-American biographer, Adina Hoffman, traveled to the poet’s ancestral village, Saffuriya (or Tzipori in Hebrew and Sephoris in Latin), which at one time was a large, agricultural town of 4,500 residents. It is now a ruin in the midst of a Jewish National Fund pine forest, replete with a plaque honoring Guatemalan national independence day! It is thus one of hundreds of such Palestinian villages ethnically cleansed in 1948.

It is only natural to compare Ali to that other, perhaps grander voice of Palestinian poetry, Mahmoud Darwish. But they are quite different. Where Darwish wrote in classical Arabic, Ali, having only four years formal schooling, writes in the everyday Arabic of the street. Where Darwish’s poems are both deeply personal and political engaged, Ali’s creep up on politics from different angles while always maintaining a primary commitment to the personal. He has the chutzpah (or perhaps naivete) to say:

There is no Israel. There is no Palestine.

For Darwish, this would be heresy, though I’m sure he would understand the impulse.

I’m including this extraordinary poem which proceeds in Ali’s inimitable sly style from a crying out for revenge to a quiet internal triumph over such human frailty. By poem’s end, the narrator, merely by ignoring the tormentor, has achieved all the revenge he needs:

REVENGE

translated by Peter Cole, Yahya Hijazi, and Gabriel LevinAt times … I wish

I could meet in a duel

the man who killed my father

and razed our home,

expelling me

into

a narrow country.

And if he killed me,

I’d rest at last,

and if I were ready—

I would take my revenge!*

But if it came to light,

when my rival appeared,

that he had a mother

waiting for him,

or a father who’d put

his right hand over

the heart’s place in his chest

whenever his son was late

even by just a quarter-hour

for a meeting they’d set—

then I would not kill him,

even if I could.*

Likewise … I

would not murder him

if it were soon made clear

that he had a brother or sisters

who loved him and constantly longed to see him.

Or if he had a wife to greet him

and children who

couldn’t bear his absence

and whom his gifts would thrill.

Or if he had

friends or companions,

neighbors he knew

or allies from prison

or a hospital room,

or classmates from his school …

asking about him

and sending him regards.*

But if he turned

out to be on his own—

cut off like a branch from a tree—

without a mother or father,

with neither a brother nor sister,

wifeless, without a child,

and without kin or neighbors or friends,

colleagues or companions,

then I’d add not a thing to his pain

within that aloneness—

not the torment of death,

and not the sorrow of passing away.

Instead I’d be content

to ignore him when I passed him by

on the street—as I

convinced myself

that paying him no attention

in itself was a kind of revenge.Nazareth

April 15, 2006

And another wonderful shorter poem, Twigs:

And, so

it has taken me

all of sixty years

to understand

that water is the finest drink,

and bread the most delicious food,

and that art is worthless

unless it plants

a measure of splendor in people’s hearts.

WHYY featured an interview with Ali’s biographer, Adina Hoffman, who wrote My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness.

A few days ago, the Nobel committee awarded the literature prize to a Swedish poet, which isn’t surprising considering that the awards are largely based in Sweden. What a pity they didn’t go farther afield to find this gem of a poet who was under their noses for decades just waiting to be discovered–until it was too late. If Israel would embrace its poets equally regardless of their ethnicity or native language, then its Palestinian writers would be able to claim their place on the world stage as they should. That they have not yet done so is yet another of the tragedies of unfulfilled promise that is contemporary Israel.

For the poetry junkies out there and those thoroughly captivated by the man, here’s more video of him reading his poetry:

Taha Muhammad Ali (with Peter Cole) from Neil Astley on Vimeo.

It doesn’t look like Haaretz has bothered to remember him either.

Gmar tov

And that’s always been one of my favourite poems of his. Nice choice!

There are so many. It was hard to choose.

Thank you for this wise and affectionate remembrance.

Thank you for presenting the videos to accompany the remembrance of Taha Muhammad Ali’s life and work. You gave a gift to all yr readers who did not know of his work or life, & an unexpected pleasure for those who did.

The only thing I would add is that he was a Palestinian as was Darwish, not Israeli. To be remembered as Palestinian and Arab poet because that was who he was.

I think you misunderstood what I meant. Ali was not just a great Israeli Palestinian poet. He was a great ISRAELI poet. Saying that he was the best poet produced by an Israeli minority does him a disservice. He was one of the great poets produced by ISRAEL.

Saying that he was Palestinian solely doesn’t do him justice either. Don’t forget he was the poet who said: “There is no Israel. There is no Palestine.” To say he was Palestinian and divorce that from his Israeliness is doing an injustice to his own self-image as a poet and citizen.

And this is a complicated man. You want to talk about steadfast? There is no moreso. He was expelled from Israel not just once (in 1948), but twice. He was captured after his first return and expelled to Jordan, but came back yet again. But when asked in a film documentary what he would do when he returns to Safuriyya, he replied: “I don’t want to return to Safuriyya. Why would I?” In other words, he is not someone who wants to recreate the past in contemporary reality. He wants to recreate Safuriyya in his poetry and in order to deal with the injustice of its destruction. But to actually return, this he doesn’t need to do. So he is not a politically engaged national or nationalist poet in the sense that Darwish is. But that doesn’t mean that he doesn’t address the same issues and struggles. He just does it in a very personal way.

Thank you very much for sharing this inspiring post.